As cities and towns passed face mask ordinances last summer to combat COVID-19, some turned to marketing and communications departments to help spread the message of the importance of wearing masks to a sometimes skeptical public.

Communication campaigns popped up in municipalities statewide – from large banners erected in downtowns to Instagram posts with local businesses and neighbors pledging to wear face coverings.

The Florence Forward Pledge program, for example, started after the city adopted an emergency face covering ordinance, requiring face coverings to be worn when people enter a business that is open to the public. The program sought to encourage businesses to commit to the safety of their employees and the public by following state and federal safety guidelines, said Hannah Davis, development manager for the City of Florence.

A Florence Forward Pledge decal hangs in a business window. Photo: City of Florence.

Each participating business received information to help keep employees and customers safe, and a door decal to remind patrons that the business was following COVID-19 safety protocols, she said.

“The 30,000-foot answer [for why the campaign was important] is that we have got to show a united front, especially with a pandemic that’s been so politicized. It’s important that we put out the facts, put out why it’s important to our community and amplify the message in a consistent way,” Davis said.

Some cities, including Florence, modeled their pledges and campaigns after Greenville, the first municipality in the state to enact a face covering ordinance. After passage, Greenville quickly pushed out its “Mask Up. Life is Waiting.” campaign, which drew on locals to explain the importance of masks to slow the spread of the virus and allow life to return to normal, said Beth Brotherton, director of communications and neighborhood relations in Greenville.

The campaign was announced by Mayor Knox White at one of the city’s media briefings with local physicians.

“We chose local, recognizable people — a mom blogger, a high school football star, a popular restaurant owner — and chose taglines that we hoped people would connect with. ‘I wear a mask because … we all miss school.’ ‘I wear a mask because … fall isn’t the same without football,’” Brotherton said.

The campaign ran at a time when schools had not yet decided on their attendance and athletic plans.

“We also included a small business owner so citizens could recognize that another closure or stay-at-home order could be devastating to entrepreneurs who were barely hanging on to their livelihoods,” Brotherton said. “We used a bride-to-be because it seemed like everywhere you looked on social media people were talking about delaying weddings, hosting them on Facebook live or limiting guests to only immediate family. The tagline was ‘I wear a mask because … I’ve dreamed of this day my whole life.’ We didn’t want to be heavy-handed. We just wanted people to think about the impacts.”

To make the campaign visible, Greenville erected 5-by-7-foot A-frame signs around downtown, along with smaller signs at entrances to local attractions. They also added streetlight banners.

“The campaign certainly got a good response on social media,” Brotherton said. “Lots of people took selfies with the posters downtown. It was fun to see how people did really connect with the message. I think the campaign, combined with the ordinance, did exactly what we hoped it would do. It made mask wearing more ‘acceptable’ and less ‘weird.’”

The face-covering campaigns around the state also drove home the importance of municipalities working with other area organizations to broaden a city’s reach.

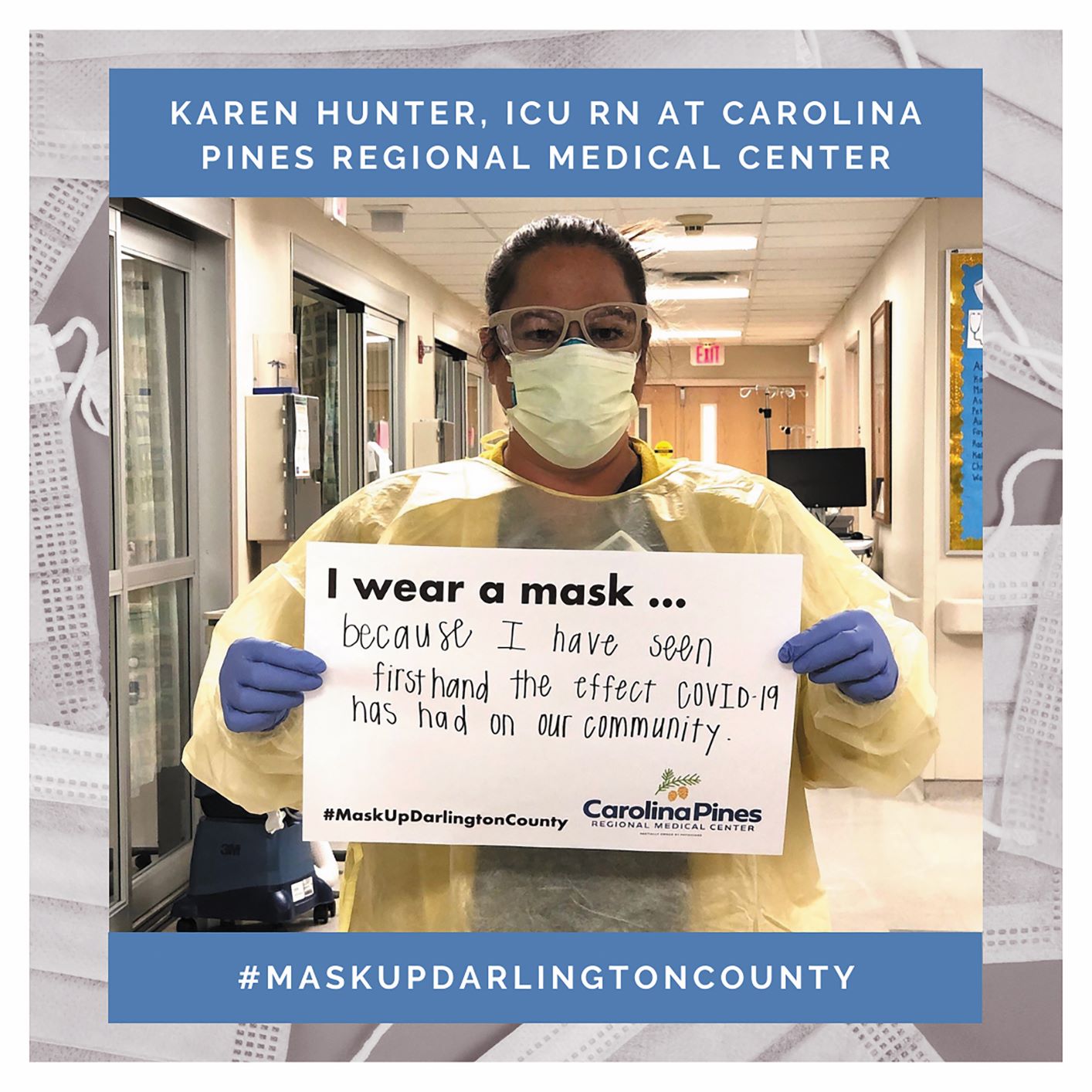

In Hartsville, which also had a mask ordinance, the city worked with Darlington County, the school district and Carolina Pines Regional Medical Center on the “Mask Up Darlington County” initiative. The collaboration began while the Darlington County School District was discussing back-to-school plans.

The “Mask Up Darlington County” effort was a partnership between Darlington County, the City of Hartsville, Carolina Pines Regional Medical Center and the Darlington County School District. Photo: City of Hartsville.

“All organizations wanted to make one large — and loud —push to encourage residents to mask up in order for COVID-19 numbers to decrease, therefore meaning students could return back to the classrooms,” said Lauren Baker, Hartsville’s director of tourism and communications.

Communications representatives from each organization met to create a consistent, branded campaign to show they were all on the same page. They used the same signs, but changed out the organizations’ logos.

“We allowed the individuals to write their own personal reasons for wearing a mask. These real-life reasons and scenarios allowed the campaign to hit home for people on different levels. These photos and videos were then dropped into one template and posted across all organizations’ social media pages,” Baker said.

According to analyses by the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control, cities with mask ordinances saw COVID-19 numbers drop during the campaigns. Looking ahead, cities say they have learned lessons from the successes and missed opportunities of the mask wearing campaigns they can build on in the future.

“The biggest lesson I learned, as a communications department of one, is the strength in collaboration,” Baker said. “While I was responsible for the scheduling, branding and posting, it was great to have other organizations feeding me a diverse group of content. This allowed the campaign to have a greater impact in the community as a whole, not just in the direct city that we serve.”

Davis said Florence was actually a few months behind with implementing its program, and an earlier start may have generated more participation than the 36 businesses that had opted in by early November.

“We need to find a more effective and efficient way to get the word out about future participation-oriented programs and convert interested parties to real users of the programs. On the plus side, we found a whole new set of skills within our staff to create these user-generated platforms utilizing GIS. In the future, we plan to implement this type of opt-in program should the need arise. We see it potentially being very useful for documenting calls for service, or hurricane response,” Davis said.

In Greenville, Brotherton said the success of the city’s efforts reminded her that public health marketing campaigns must be simple, real, personal and not “boring.”

Dr. Eric Ossmann speaks at a press conference in front of Greenville’s mask campaign signs. Photo: City of Greenville.

“Numbers and data are important and can certainly help you tell the story, but at the end of the day it’s about showing people why they should give a darn. Answering the question, ‘Why should I care?’ In this case you should care not only because you have elderly parents who have been unable to see their grandkids, or people with preexisting medical conditions who are at severe risk of complications or death if exposed, but because we desire the more everyday things of going to a ballgame, eating at our favorite restaurant and being able to go to school to see friends,” Brotherton said.

Greenville is now taking lessons learned from the public health campaign to launch new campaigns. Brotherton said when her office got an assignment for a tree preservation campaign, she was told, “‘We were thinking something like the ‘mask up’ campaign.’ So, I’m thinking you’ll see a lot more photos of real people in relatable situations coming from the City of Greenville.”