Built as the First National Bank of Camden at the start of the 20th century, the structure at 1025 Broad St. in Camden, struggled to survive as the decades passed. Windows were bricked in, upper floors fell into disuse, and the roof started to fail.

In 2019, Wes and Laurie Parks bought the building, with Laurie envisioning it as a self-serve wine bar. Their rehabilitation has divided it up for multiple functions, including the bar, an office and apartments, and made use of multiple tax credits, including the South Carolina Abandoned Buildings Revitalization Act. The tax credit offered by the abandoned buildings act, Wes Parks said, can help make projects like this bank revitalization possible.

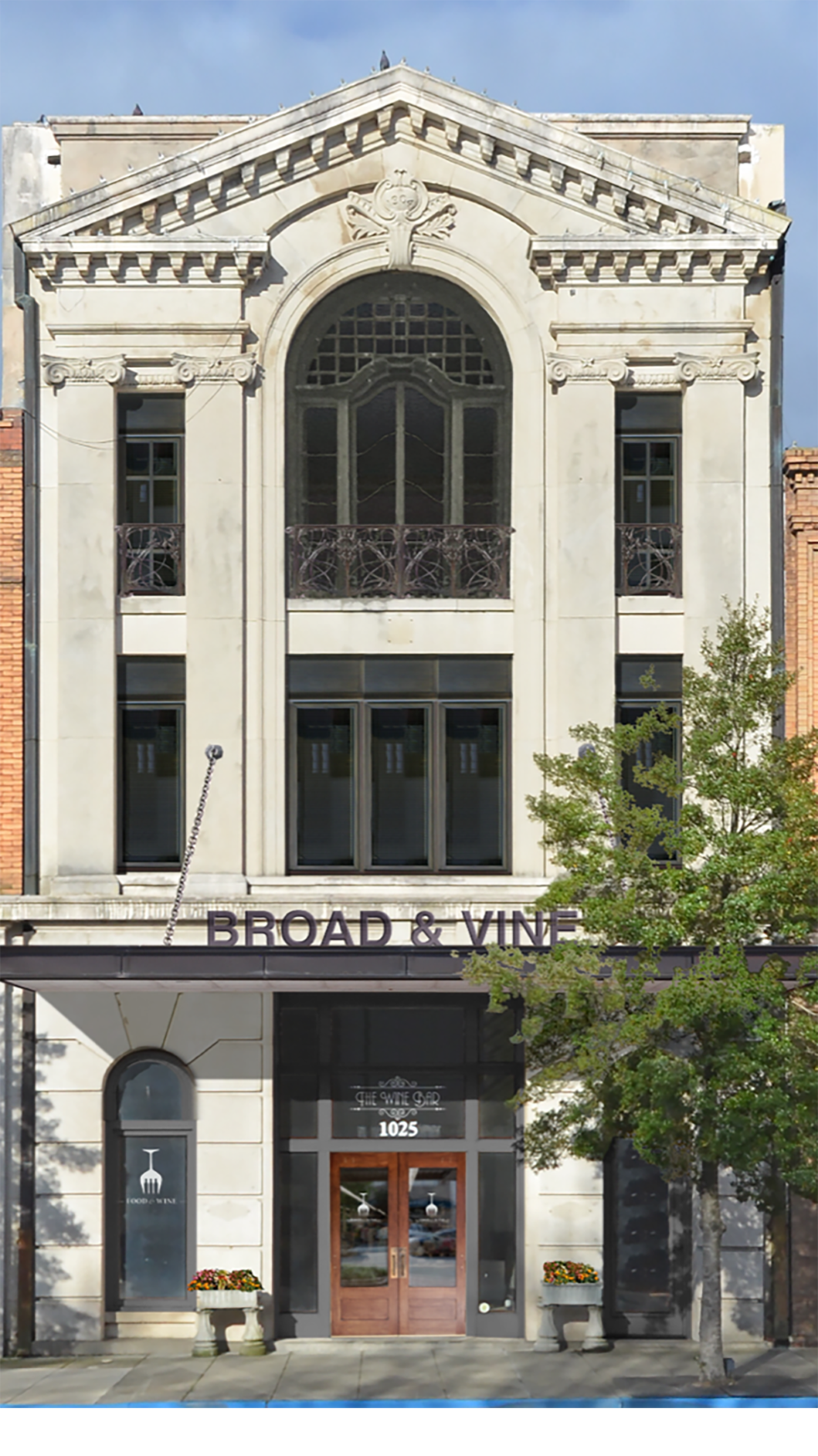

This photo shows the previous state of 1025 Broad Street, while the rendering shows its appearance after renovation. Photos: P&P Investment Partners, LLC.

“Many of these properties are so dilapidated that the appraisal won’t meet what the rehab costs are. That’s the case in this situation,” he said. “If we didn’t have the tax incentives to do the project, it wouldn’t be financially feasible, so the banks wouldn’t have loaned money.”

The credit requires 66% of a building to be abandoned for five years to be eligible. A developer can choose to use a state income tax credit or a property tax credit with the consent of the affected taxing entities. The taxing entity, such as a city council, also has to approve a resolution certifying that the structure meets the five-year requirement before work begins.

With the abandoned buildings tax credit, buildings can be divided up by floor for eligibility, as happened in the case of 1025 Broad St. Up to seven separate floors can be considered seven separate projects eligible for the credit. To be eligible for the credit, projects must redevelop these separated-out floors for exclusive use as a residential apartment or apartments.

For much of the interior of the structure, Parks said, they wanted “to have that historical feel, like I’m still in that bank.”

The top floor appears with a bricked-in window before renovation, while the renovated lobby shows its history as a bank. Photos: P&P Investment Partners, LLC.

Original tilework discovered in the building provided an opportunity for the renovation to use matching, authentic tiles. The renovation included custom-built windows on the upper floors to match the historic design.

In historic downtowns, two- and three-floor buildings with the upper windows bricked in are a common sight, said Camden’s Director of Planning Shawn Putnam.

A renovation such as the one at 1025 Broad St., with the windows restored, “makes such a difference, when you look down the street, to give it that historic feel,” he said.

The city has three incentive efforts, according to Putnam, including a façade grant program and a Bailey Bill program, which initially brought the city into a conversation with the Parks for renovation efforts. It also has an Economic Development Incentive Program that allows the city council to approve incentives in the form of fee reimbursements for up to five years.

Tax credits, like the abandoned buildings credit, promote the reuse of existing structures, Putnam said, which can be good for a community’s historic fabric and the environment.

“In a historic downtown, you want to preserve as many historic buildings as you can that are feasible,” Putnam said. “It’s really a win-win program, there’s really no downside to either the city or the developer for using these tax credits.”